photography Peter Cox >>>

De tentoonstelling Beyond Generations toont werk van verschillende generaties ontwerpers die studeerden aan Design Academy Eindhoven.

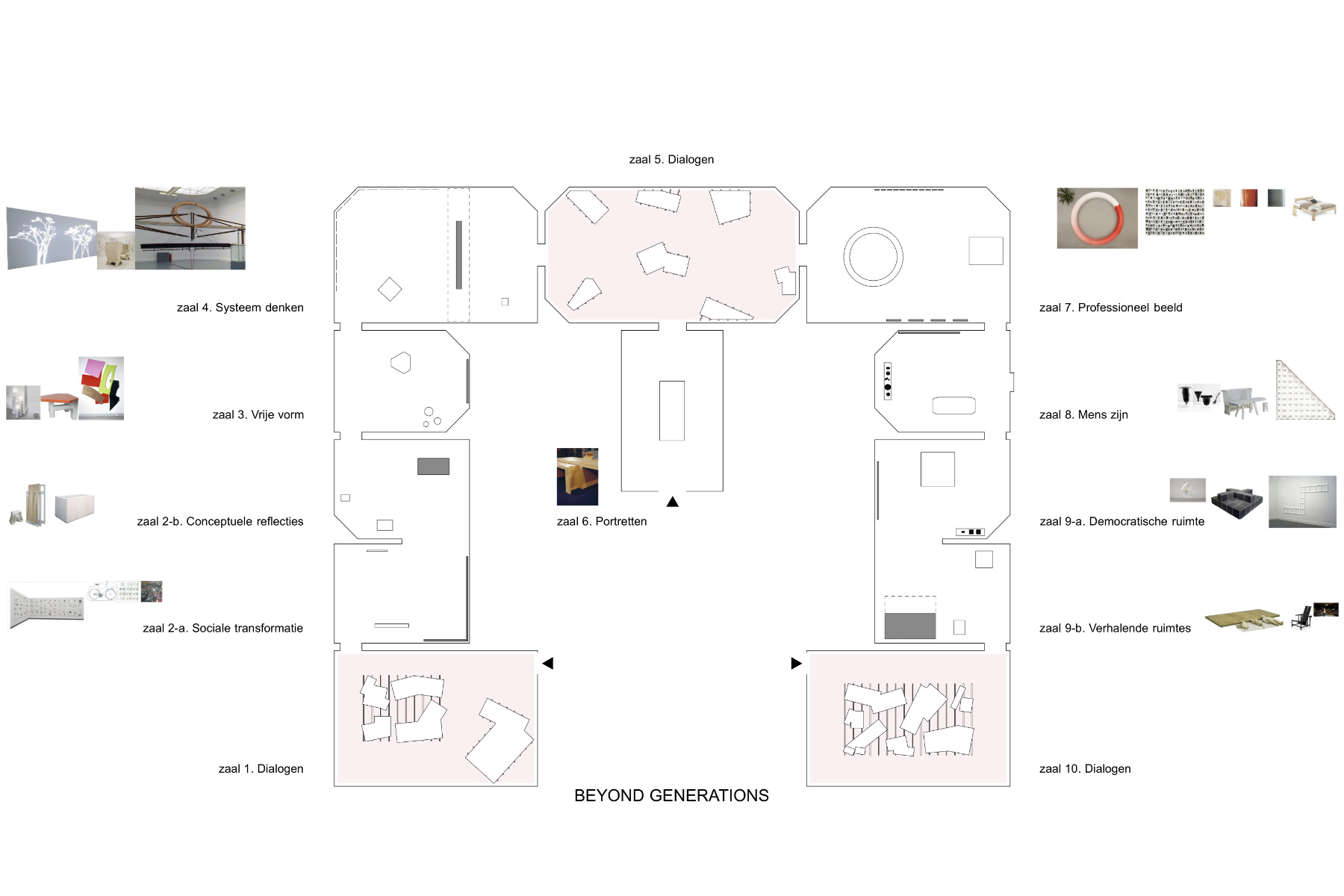

De inhoud van het begrip design verandert voortdurend. Elke generatie ontwerpers ontwikkelt een eigen invulling, van nuttige functionaliteit tot luxe schoonheid. Veel jonge ontwerpers benaderen design inmiddels als een vorm van politieke en maatschappelijke interventie. Beyond Generations toont hoe generaties ontwerpers de afgelopen 70 jaar visies ontwikkelen en het vakgebied veranderen door met elkaar in gesprek te gaan. Rond acht kernthema’s worden hun dialogen tastbaar gemaakt. Werken uit de collectie van het Van Abbemuseum fungeren als maatschappelijke en culturele spiegel. In drie zalen ontsnapt de dialoog zelfs aan een thema en regeert het associatieve gesprek dat zo vaak de motor voor vernieuwing blijkt te zijn. In deze zalen staan meerdere een-op-een-gesprekken tussen ontwerpers naast elkaar. Wat veel ontwerpers gemeen hebben is de wens om uniek te zijn. En toch staan ze onbewust op elkaars schouders.

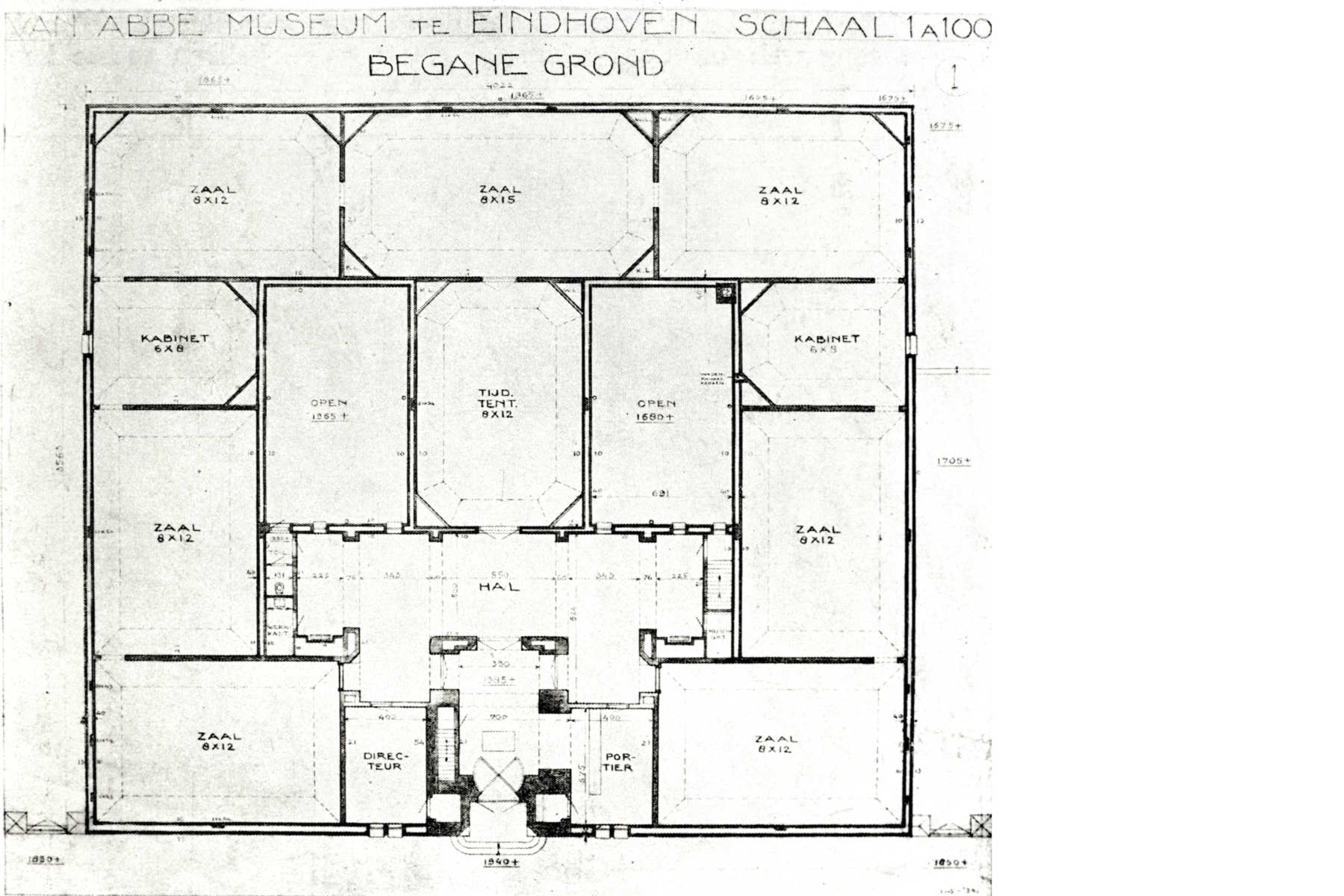

De karakteristieke plattegrond van het Van Abbe Museum is in mijn geheugen gegrift. Archetypisch geworden voor 'het museum'. Op een steenworp afstand van de AIVE, de voorloper van de Design Academy Eindhoven, was het museum voor mijn generaties dé plek om in contact te komen met autonone kunst. Als student industrieel ontwerpen in de jaren '80, waren de toonaangevende tentoonstellingen onder directeur Rudi Fuchs, de eerste belangrijke momenten van reflectie en bezinning.

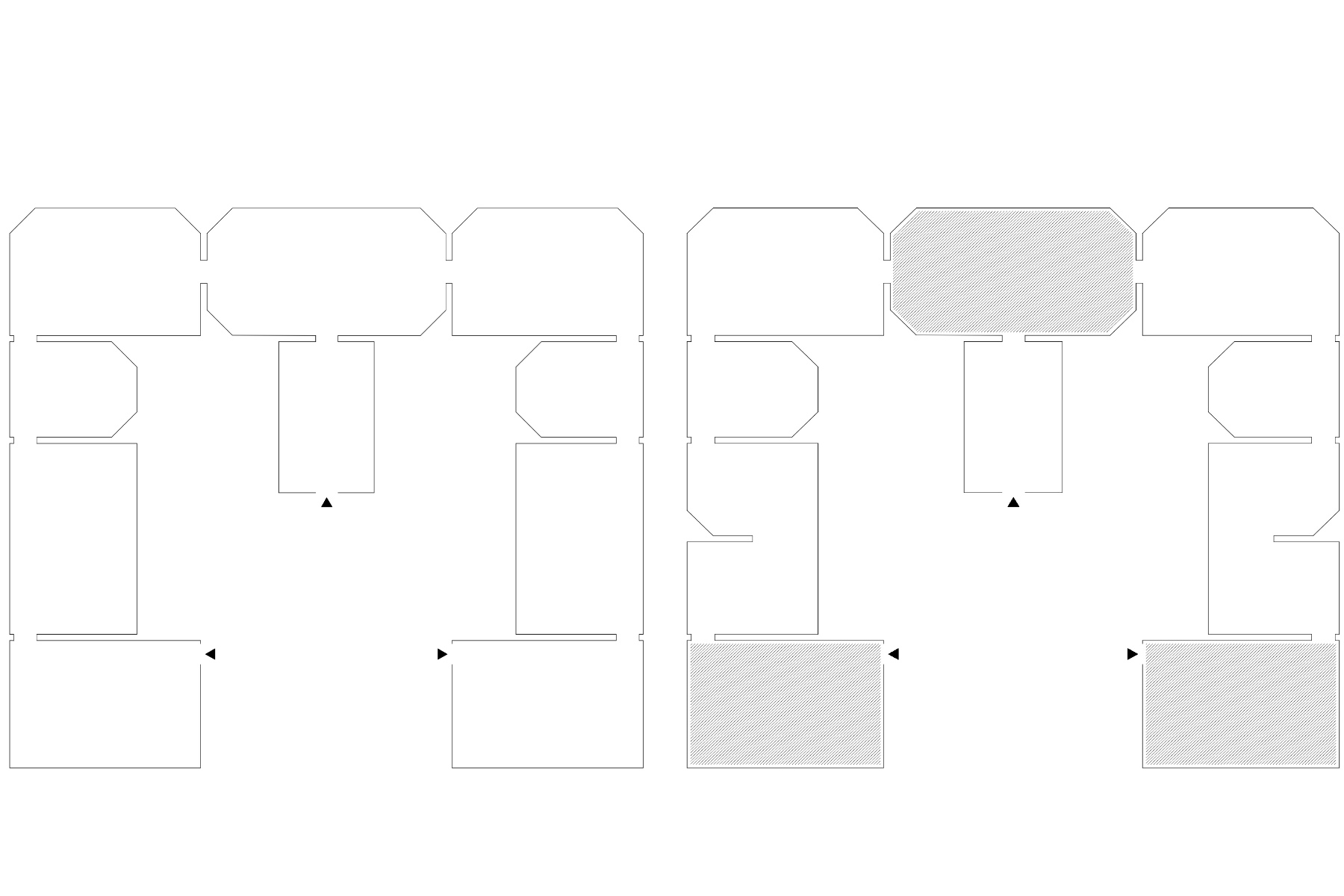

Door het plaatsen van twee 'hoeken', gespiegeld aan de hoeken in de bestaande zalen, ontstaan twee extra plekken. Nodig om ruimte te bieden aan het aantal thema's in de tentoonstelling Beyond Generations. Ondanks deze 'grove' ingreep in de plattegrond van de oudbouw, blijft de ruimtelijke ervaring van het museum vrijwel onaangetast.

photo BG

photo BG

photo BG

Zaal 1. Dialogen

Zaal 1. Dialogen

Zaal 1. Dialogen

Zaal 1. Dialogen

Zaal 1. Dialogen

Zaal 2a. Social Transformation Since the 70s

Products became vehicles for change. They no longer just related to industry or commerce, they also inhabited a place in our cultural world. Interaction with objects influences human behaviour and therefore design can also be utilised as a tool for instigating social change. Design as a model for social transformation through creative impact. Recently, this position has become visible in the graduation shows. The graduation projects show a range of topics varying from social tools and care through to waste collection systems. These projects have a noticeable effect on society at large. Like Christien Meindertsma’s work, which brought a smile to our faces with the flash mob for Loes Veenstra, or projects designed specifically for a group of people, such as the detainees with whom Anne Pabon worked to help them qualify as TIG welders.

Zaal 2b. Conceptual Reflections Since the late 80s

An object was no longer just a set of functional requirements, it became an entity that interacted with people, human-centred and with a conceptual and rational awareness. Design proposals were expected to explore conceptual expressions in material, in shape or in structure. In 1987 the Academy introduced the ‘Man and’ model for their departments and the human-centred approach to design became a focal point in the educational system. Droog Design was established in 1993 by Gijs Bakker and Renny Ramakers to promote a conceptual and humorous reflection about the discipline of design.

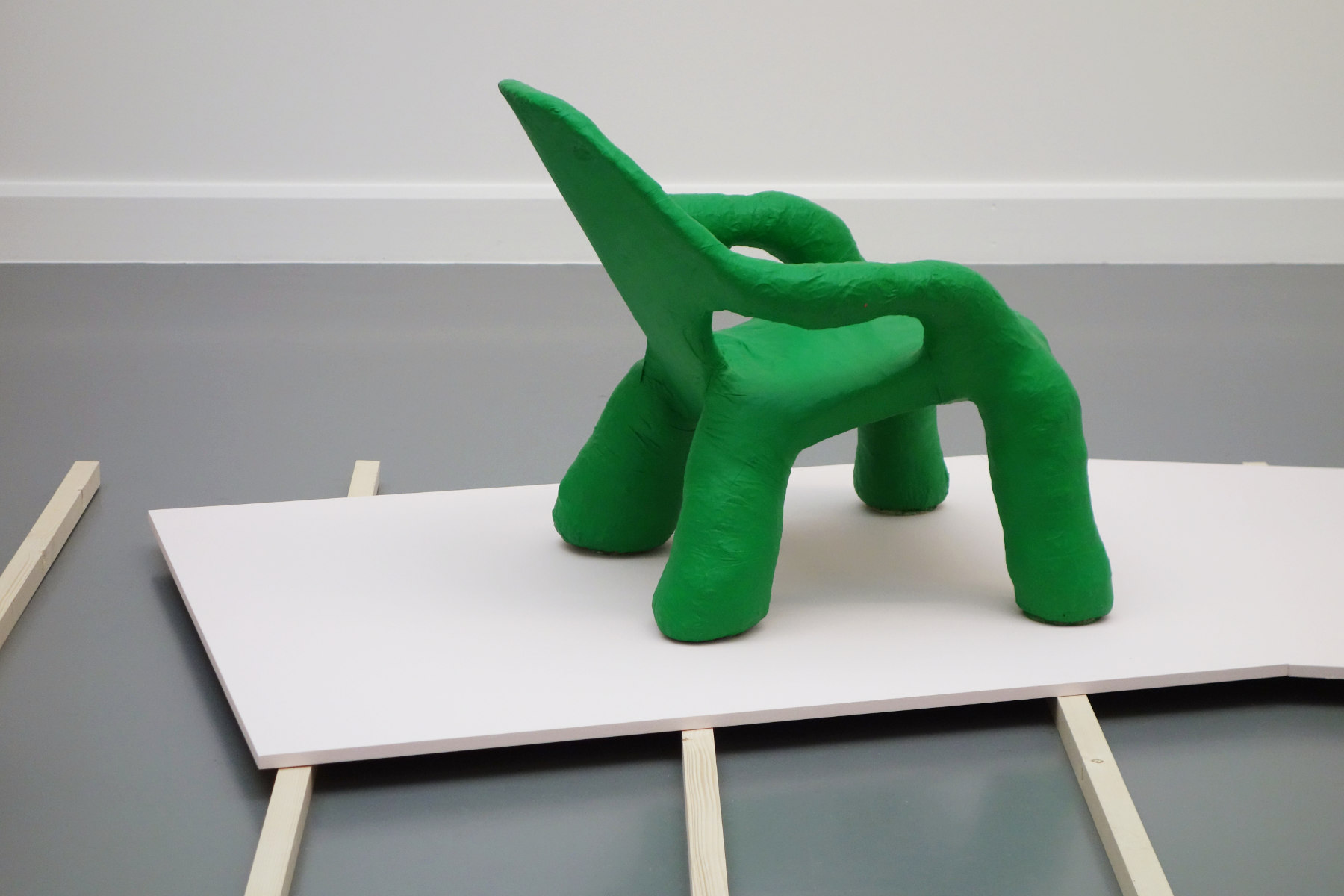

Zaal 3. Free Form Since the 80s

The impact of visual media became increasingly apparent in the seventies. We were living in a culture of visual images. International design groups like Memphis and Alchymia researched this phenomenon through creating a new associative visual language employing free and expressive forms: postmodern design. In the Netherlands, the foundation Products of Imagination – founded by Ed Annink and Christine de Baan in 1987 – promoted this new attitude. They organised exhibitions and presentations in galleries where experiments with form were presented. Shape is no longer a logical solution to the problem, rather an effect to work with. Rational qualities of industrial process are opposed by personal expressions of form and aesthetics. This is also when designers started to make and sell products themselves: the self-producing designer made its entrance to Dutch design. Experiments with materials and concepts became mainstream, just like the Set Up Shade by Marcel Wanders. He designed the lamp through collecting and assembling second-hand shades into signature pieces and ignoring the trends in interior design of the time.

Zaal 4. System Thinking Since the 70s

A design object does not stand alone, but is always part of a larger structure. It is part of an ecosystem, a production process or a 24-hour cycle of day and night. In his work, Van Bakel investigated and employed the holistic system to create a more appropriate design for the world. The world is a closed system in which design can establish new harmonies. Design is as much a movement and an energy as it is a final solution. This vision of how design can create new conditions can be found in the new Interpolis headquarters (designed by Kho Liang ie Associates in 1997) for which Studio Makkink & Bey designed the Ear Chairs. The new office was devoid of cubicles popular at the time. Through creating new working conditions, ‘the flexible office’, as it was called, caused a small revolution in office design.

Zaal 5. Dialogen

Zaal 5. Dialogen

Zaal 5. Dialogen

Zaal 5. Dialogen

Zaal 5. Dialogen

Zaal 5. Dialogen

Zaal 5. Dialogen

Zaal 5. Dialogen

Zaal 7. Professional Display In the 50s

The Akademie voor Industriële Vormgeving Eindhoven was founded (1947) during the progressive period of reconstruction in the fifties. Design matured to become a professional discipline and outgrew purely industry-focused production. Since such an institution as a ‘design academy’ had never existed in the Netherlands, the first director Rene Smeets embarked on a research trip to America. He was struck by the mindset that ‘design sells’ and met with the conviction that design could improve functionality; that it creates style and increases sales. An ‘appropriately shaped’ design can even outlast temporary trends and enjoy years of popularity, such as Auping’s Auronde bed – 40 years on, it is still a commercial success.

The academy was founded in close collaboration with Philips. As industry underwent major changes through the years, the discourse about professionalism morphed to become a critical reflection on the profession itself. Designers were searching for loopholes in mass-production and experimenting with new approaches and materials. Exploring the consequences of repetition, mass production and coping with mass consumption and resources becoming scarce — as Chris Kabel’s Stack Ring exemplified: 250 identical stools each in a different shade of red.

Zaal 8. Being Human Since 00s

Design creates the environment in which we live and with which we live, creating the conditions of our human condition. Design influences the way in which we perceive our surroundings, from the light that falls on our retina, the textures we touch to the spatial relations between objects and their environment. This novel approach serves as a guide for creating sensory, tactile and visual experiences. Product design has become a sensation to remind us of our human state and put us in touch with our emotions and sense of wellbeing. Ilse Crawford set the stage for the designer who creates products and interiors that enhance and support our humanity. With the Man and Well Being department, she focuses attention on the materials and textures in our everyday surroundings and paves the way for more sensitive designers.

Zaal 9a. Democratic Space Since the 70s

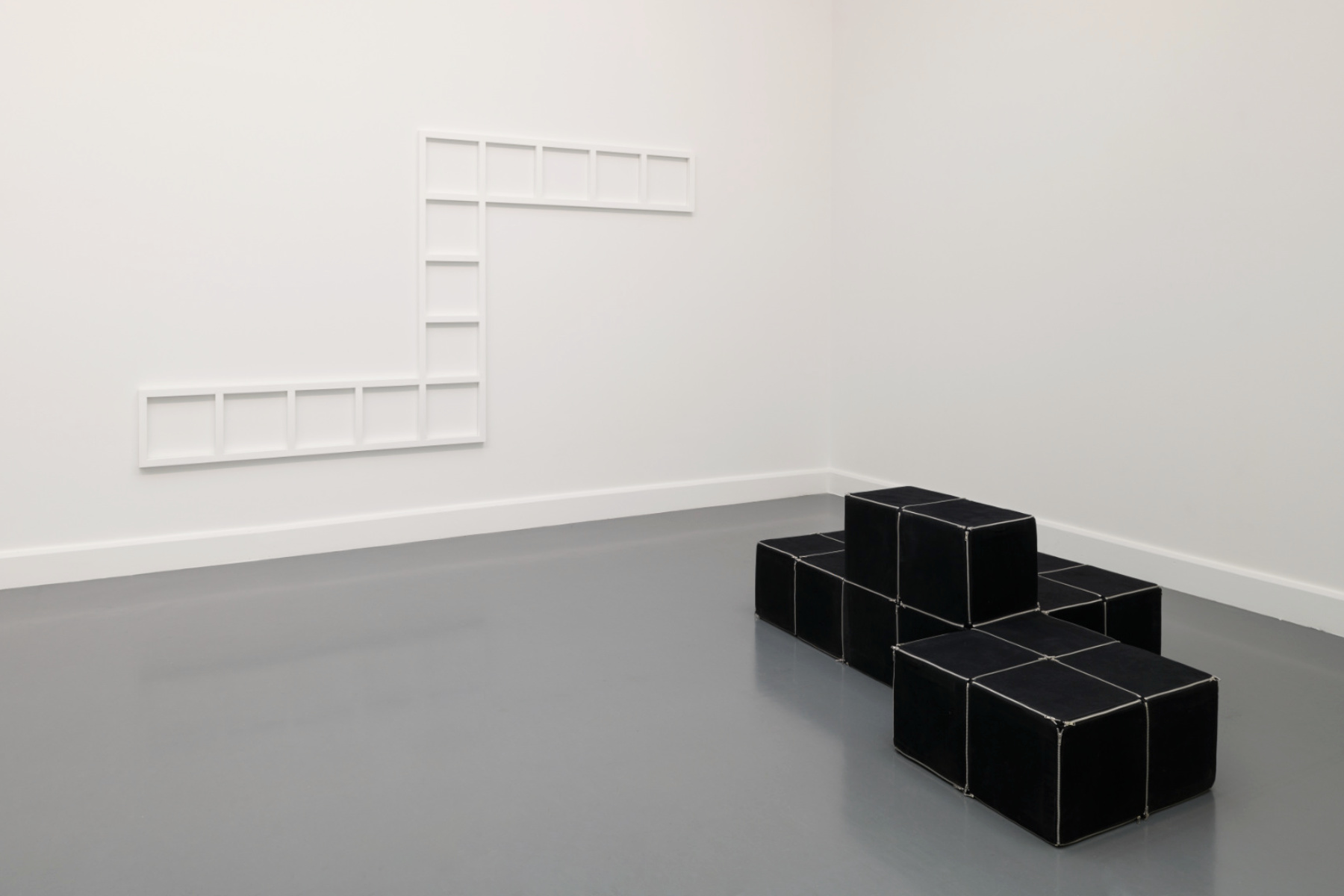

Modern functionality can be rather constraining, especially with individual freedom coming into bloom. The seventies were marked by student protests and the rise of the counter movement. As a reaction, designers looked for new solutions that offer both structure and freedom. Grids or repetitive elements provided this freedom. Slothouber and Graatsma’s work is a perfect example of this. Their cubic constructions and product designs are both universal and flexible: they can be set up in many different ways. Eventually this structural approach democratised production processes employing Do-It-Yourself principles, enabling users to adapt and configure products to their own needs. Hacking Households is a recent example of a group of young designers who designed products that can be easily assembled and disassembled in an attempt to show an alternative to products that end up in a landfill.

Zaal 9b. Story Spaces Since the 90s

Once our experiences had come to span multiple media channels and formats, there was a need to review the coherent experience. Designers approached their work from a personal motivation and vision and as such opened their field to the users. Customers were invited to join the story and relate to products in a new way. Narrative and emotional elements created a coherent and compelling experience and design became a tool to evoke emotions like fear, joy, happiness, sadness or anger. Designers became famous through their iconic collections instead of opting for a career in industry. Maarten Baas’ Smoke collection was perhaps the first example of this. He has an autonomous position in relation to his clients and launches his collections in-house, and his work is exhibited in galleries. Through his products, he invites you into his world.

Zaal 10. Dialogen

Zaal 10. Dialogen

Zaal 10. Dialogen

Zaal 10. Dialogen

Zaal 10. Dialogen